I spent an afternoon with Phil Spector in his suite at London’s Dorchester Hotel. Spector was always, to put it mildly, eccentric. But he could also be charming and lucid. I came away with at least four great tales (you’re reading them here for the first time).

I was there because Apple Records, the Beatles’ label, was reissuing A Christmas Gift For You, Spector’s fabulous 1963 album which I had bought on day of release, aged 14. Now, here I was, nine years later, in the room with the man himself.

Going off on a bit of a tangent, here’s an insight into the mind of a tabloid journalist. Also in the room was the Daily Express ‘music columnist’. Believe me, this person knew nothing about music. She was an embarrassment. (I was chatting to Harry Nilsson one day, when this buffoon cut across me with: “So, Nilsson, how did you come to write Without You?” Very quietly, Harry replied: “I didn’t.” And for her, the ‘journalist’, that was the story: Number One Hit Man Didn’t Write Song).

So, back at the Dorchester, Phil Spector has decided to put us all at ease by telling a funny story. The previous evening he and a couple of Rolling Stones (Jagger and Richards) and friends had gone for dinner in the hotel restaurant. Some American diners had taken exception to these long haired, dirty rock and rollers in their midst and made their feelings known both to the maître d’ and to the dirty rock and rollers themselves.

The Stones, according to Phil, were British manners personified. Keith Richards tried to mollify the tourists, showing how civilised he was by attempting humour to defuse the situation. But the Yanks stayed angry, and eventually stormed out, refusing to pay.

Now, here’s the tabloid mind for you: before he even finished the story, your Daily Express correspondent asked Spector if she could use the phone in his suite. Right there in front of us, she dialled out and demanded, “Give me the news desk”. Then she started to dictate her story: “Rolling Stones and American Producer in posh restaurant fight”.

Right there in front of us! No shame, no hint of embarrassment.

Spector walked over, took the phone out of her hand and replaced it on the stand. He put his hand on her shoulder, politely guided her to the door saying, “Please do that outside” and showed her out.

Unphased, Spector continued to be the perfect host, before excusing himself to make a phone call. I wasn’t taking much notice until I heard him say: “Get me Muhammad Ali.” Ali – possibly my biggest hero – was fighting that night in America and Phil wanted tickets to a cinema relay of the fight in London.

“Hey, Muhammad, how are you, Champ? Listen, can you arrange some tickets for me to see the fight in London? Great, yeah I know you’re busy. Go get ’em Champ.”

I was so naive I believed it. It was years before I realised that this was a perfect piece of Spector grandstanding. The idea that a man preparing himself for a fight, and on his way to regaining the World Heavyweight Title, could be got on the phone in a couple of minutes of 1970s transatlantic telephony – well, you get my drift.

But that’s the kind of chutzpah that got the young genius into the hit-making business in the first place.

Later, I told him I was a songwriter and had been an admirer ever since I made the connection between Zip A Dee Doo Dah (by Bob. B. Soxx & The Blue Jeans) and Da Doo Ron Ron (by the Crystals). By the time the Ronettes’ Be My Baby arrived I was completely hooked on Spector’s Wall Of Sound.

I don’t even remember how I knew he was the guy behind these records. The concept of ‘the producer’ was unknown to the public pre-Spector. But in 1963, within three records I knew who Phil Spector was, and I excitedly bought his Christmas Album totally on faith.

So, naturally, I asked him to divulge some secrets. Well, he said, one of his tricks was to record, say, the drums. Then he would feed them back out into the studio and put microphones in strategic places to get that big, bouncy echo.

It took me just two years to discover he was snowing me. I was at AIR Studios with Mott The Hoople and they wanted the Spector sound. Their engineer Bill Price was explaining how it could be achieved. I said, “No, Bill. This is how he did it”. We argued back and forth and finally, exasperated, I said: “Look Bill, I didn’t want to have to say this, but Phil Spector himself told me this is how he did it!”

He looked at me like a hole had just opened up in his world. “But he told me he did it THIS way!”

I’d love to be able to report that we both fell about laughing. In fact I felt deeply embarrassed. I’d thought I was in possession of a magical piece of knowledge, but the Wizard of Phil had just made up different stuff to keep his secrets safe.

I should have known better, because Spector did tell me one very obvious tall story at The Dorchester. At the end of the Christmas album is a sweet, string-laden Silent Night over which he speaks a little homily to Christmas. “The union called a strike just before that session,” he told me, “so I had to go into the studio and overdub 16 violin parts, one at a time.”

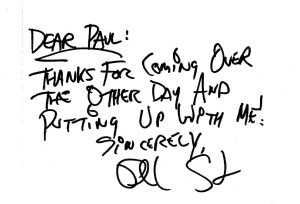

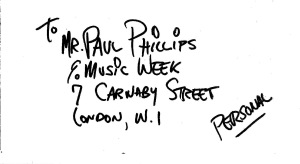

It’s just as well I have never subscribed to the idea that my heroes should live up to my personal expectations. But at least he sent a handwritten note, in a handwritten envelope – what more could you ask?

In truth, all I ask of my heroes is that they thrill me from time to time with their genius. And Phil Spector was a genius in the limited sphere that is pop music.

Which brings me to this week’s song, a cover version.

There are almost as many reasons for making a cover version as there are cover versions. You do it because you love the song as written; or because you think it will be a hit; or because you’ve seen something in it that no-one has seen before.

Phil Spector’s You’ve Lost That Loving Feeling (co-written with Barry Mann and Cynthia Weill) is a song that’s been covered countless times, a dramatic song that singers use to show off their power and range. I’ve never had much power as a singer, and my range has gone with the wind in the past two decades.

But what a song! And I’ve always loved singing it. So I challenged myself to approach it in a way where my limitations wouldn’t be an issue. What I came up with was: ‘How would Norah Jones do it?’ And my answer was: she would remove all the drama and simply rely on the song to tell its own story.

So that’s what I tried to do. And guess what? It’s impossible. The drama is all there, in the writing. It’s really, really hard to sing it low-key. I manage it, through an act of will. You’ll hear that I barely raise my voice. But even Norah Jones, the most understated singer I can think of, would struggle to remove all the drama. Have a listen and let me know, please, what you think.

And for the aspiring songwriters and producers out there, here’s a second version with the drums and reverb removed.

You’ll hear that it begins to feel even more intimate, but still no less dramatic. For a similar (but infinitely better) example of the low key approach to a dramatic song, have a look at Katie Melua singing Diamonds Are Forever, just her and her guitar. Whether you like her or not, this is a stunning performance.

Great story as ever! I love the second recording (without the drums and reverb – what ever that is? the new furniture in your room?). Did you ever get to the bottom of how Phil recorded his special sound then?

LikeLike

I did, but if you think I’m giving up that kind of info here ……..

LikeLike

Good version. Reminds me of the Walker Brothers’ “No Regrets”. I take it you’re a Scott Walker fan.

LikeLike

Ah Neil, you’ll have to wait for the Scott Walker story!

LikeLike

Yes, I prefer the simpler mix, Paul, Have only heard the first version before – you were going to put it on the Divorce album weren’t you? (Did I advise not to include covers on it? Can’t remember). Fab stories about PS. The Great Deflector.

LikeLike

I was going to put it on Now That’s What I Call Divorce. It was a segue from One Of Those Days, using the same piano part. (So now there are two entirely separate tracks where that piano appears!). And you did, indeed, tell me to leave off the covers – one of which was one of your own songs. Oh, the sacrifice!

LikeLike

I look forward to seeing the release of your version of my song one day, Paul! xx

LikeLike